Representatives of a battered and stressed medical profession gathered in Montreal and virtually last week for the 7th annual Canadian Conference on Physician Health (CCPH) – the first such meeting in four years.

Acknowledging the tremendous pressures facing physicians today, the 450 delegates in attendance – the largest ever at such a meeting – heard about the wide variety of initiatives underway to address physician health and well-being both at the individual and at the system level.

“Medicine has changed. The world around us has changed but we are all here to discuss important issues,” said Dr. Jeff Blackmer, chief medical officer and executive vice president of global health for the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), which hosted the meeting. “Many of us are stretched so incredibly then (and) have been targets of harassment and bullying at work and in training programs,” CMA President Dr. Kathleen Ross added.

Later in the meeting, Dr. Ross released a statement referring specifically to the current conflict in the Middle East. “The Hamas-Israel conflict is causing significant tensions for Jewish and Palestinian physicians, with many experiencing antisemitism, racism, Islamophobia and other forms of aggression,” the statement noted.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and its hugely negative impact on physicians was also referenced repeatedly. “COVID is not over it has a lingering presence. It has altered our ability to offer quality patient care … and we will never recover,” said opening keynote speaker, Dr. Jane Lemaire, co-director of WellDoc Alberta.

What emerged very clearly this year was the recognition of how interlinked the well-being of physicians is with the healthcare system as a whole and the health of the patients of which they care. “We are caught in a vicious cycle of work overload, burnout and attrition of the health workforce which has critical population health and health system impacts,” said Dr. Ivy Bourgeault, leader of the Canadian Health Workforce Network.

At one point in the meeting, an emergency physician from Montreal rose to ask why it was so hard to persuade people that good physician health translates into better patient outcomes.

Dr. Edward Spilg, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa noted that a decade ago individual resilience was identified as the way physicians could best deal with wellbeing issues. Now, he said, there is a recognition that system-level interventions are essential. Dr. Lemaire said a multi-pronged approach to culture change is required to improve physician well-being and the healthcare system must support such a change.

While much of the focus of the meeting was on these system-level approaches, some sessions also dealt with how individual doctors could deal with the stress of medical practice today. In a keynote address, Dr. Kristen Neff, a clinical psychologist at the University of Texas, Austin advocated self-compassion consisting of “kindness, mindfulness and common humanity”. In another session, Collingwood family physician Dr. Caroline Bowman who has been diagnosed with MS discussed shame resilience as a missing component of physician wellness.

A focus on improving the well-being of medical learners and the environment of academic medicine came from two sessions discussing the Okanagan Charter, an international framework to support well-being at academic centres. Deans of all 17 Canadian medical schools have committed to following the charter, said Dr. Melanie Lewis, chief wellness officer at the University of Alberta. But she added only 12 of the 17 schools (soon to be 13) have formally adopted the charter to date and she is the only person to currently hold the position of chief wellness officer at a medical school.

The ambivalence with which many physicians view practising medicine today was encapsulated in a plenary session at the conclusion of the conference where speakers engaged in a formal debate on whether there are still compelling reasons to practise despite the challenges involved.

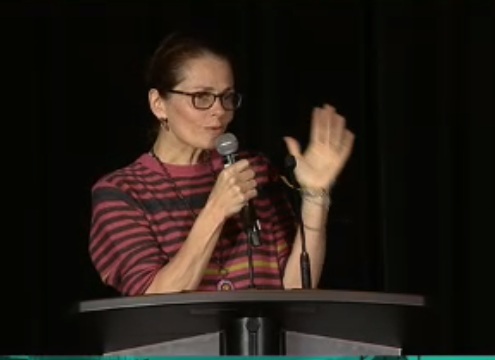

Manitoba physician and best-selling author Dr. Jillian Horton who moderated the debate noted both that “we leave jobs we love because they have become undo-able,” and that “most of us are here because we are looking for reasons to continue to do what we do no matter how difficult is.”

“The healthcare system values efficiency over patient care and values data over relationships. The painful reality is very little money and very little decision-making effort goes into our well-being,” said Dr. Julie Maggi, director of faculty wellness at the Temerty School of Medicine, University of Toronto, one of the two physicians charged with arguing the futility of continuing to practise.

Tasked with arguing in favour of continuing to practise, Dr. Saleem Razeck, professor of pediatrics at the University of British Columbia talked about the satisfaction of being a physician even with “a full bladder, empty stomach and dry mouth.”

“We are at the precipice of greatness,” said his debating colleague Dr. Andrew Ajisebutu, a neurosurgery resident at the University of Manitoba, in noting all the current advances in medicine. “At times the job does suck, but the profession does not.”

(Image: Dr. Jillian Horton moderates final plenary at CCPH 2023)